I have had the good fortune to travel all over the world—for both business and pleasure, not that those are mutually exclusive. This blog is about my unique experiences around the globe. It is not intended as a paean to the wonders of the locales themselves, as there already exist volumes that more than do justice to the magnificence of virtually every corner of this earth. Here, I simply recount small, personal moments of surprise, embarrassment, stupidity, excitement, fear, heroics, and other stuff like that.

I have had the good fortune to travel all over the world—for both business and pleasure, not that those are mutually exclusive. This blog is about my unique experiences around the globe. It is not intended as a paean to the wonders of the locales themselves, as there already exist volumes that more than do justice to the magnificence of virtually every corner of this earth. Here, I simply recount small, personal moments of surprise, embarrassment, stupidity, excitement, fear, heroics, and other stuff like that.

* * *

Beijing, China…May 1998. Notwithstanding the beauty of Paris, the bustle of Tokyo, the nobility of London, or the sheer presence of New York, Beijing is perhaps my favorite city in the world. No other city has ever transported me, both literally and figuratively, to the heights of mental and sensory acuity that I experienced there.

To wander for hours through the centuries old Forbidden City and imagine what it was like to be the last Emperor or for that matter the first, who resided there some 500 years earlier, throngs of followers stretched out in homage before him, concubines and eunuchs attending to his every whim; it is a truly magical place.

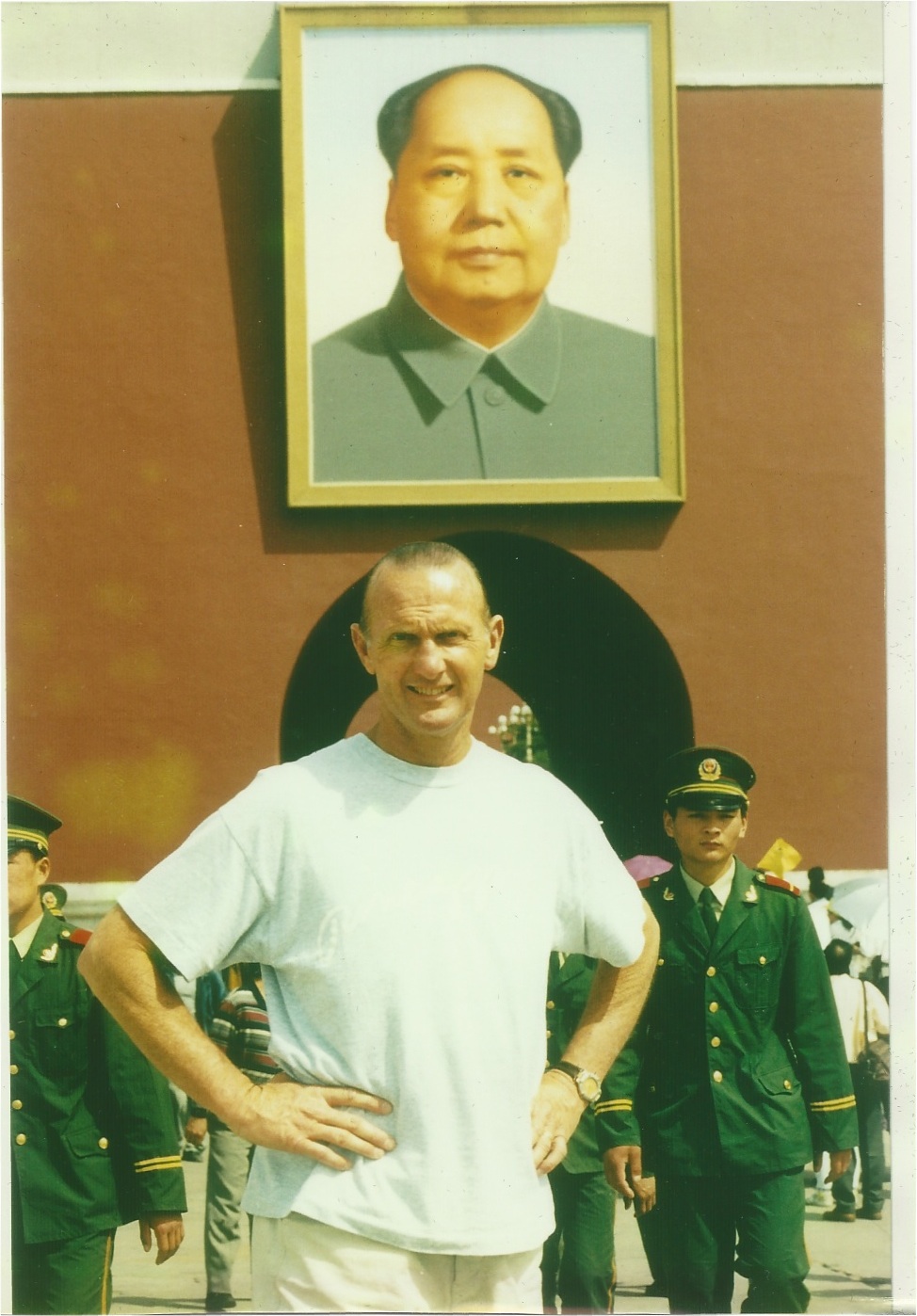

Located in the center of Beijing, just around the corner from our hotel, I would jog each morning past the entrance to this city within a city, and consider life outside its walls for the common people who were forbidden to enter the Emperor’s world of secrecy and mystery. Then I look up at the enormous framed portrait of Chairman Mao overhanging the main gate, as workers clad in drab tunic style Mao suits sweep the pre-dawn streets—vivid reminders of China’s communist mindset, still fresh and dominating despite two decades of the country being open to westerners like me.

I continue my jog through Tiananmen Square and am immediately transported to that iconic moment, just nine years earlier, when a lone student stood before a column of 50-ton Chinese military tanks in a protest that would have been inconceivable to generations past, resulted in a massacre of student protestors, and moved China another painful step toward its future.

Later in the day, Sande and I will ride our bikes to the Temple of Confucious before stopping for lunch at McDonald’s, at which point a mild rumble is felt on the ground below our feet, as Confucious, Mao Tse-Tung and every Emperor in China’s thousands-years history undoubtedly turns over in his grave.

Yes, Mickey D’s is alive and well everywhere! And Sande and I more than lived up to the American stereotype, arriving on the slick new bikes provided by our hotel. As if our tall, blonde-headed selves didn’t stand out enough from the millions of short, dark-haired Chinese riding on bikes that looked like they’d been around since Chiang Kai-shek was a kid, we rode bikes with more shiny chrome than my old Shelby. But the best part of our stop at McDonald’s was the Chinaman who caught Sande’s eye by pointing at me, saying something we obviously could not understand, while gesturing with great animation about some aspect of my size. My height? My shoes? My package? Who knew?

On the way back to our hotel that afternoon, I thought (not a very bright thought and one which Sande was outspokenly against) we should take a quick spin through one of the hutongs, the courtyard-like neighborhoods where the common (poor) Chinese live. In hindsight, it was probably akin to “taking a spin” through the drug-laden projects of Baltimore, made famous by HBO’s The Wire. Two things were quickly apparent as we turned off a main street and into the hutong. One, now we REALLY stood out and clearly had no business being there. Indeed, one old man (don’t know if he was a little crazy or just pissed off) actually swung at Sande as she pedaled, making her now a lot pissed off at me for leading us into a place I didn’t know how to get out of, which leads to my second point. Many hutongs, this one included, have just one way in and out. We’d have to pedal out the way we came in, risking either another swing from the crazy old man, or worse. Maybe the whole hutong population would block our exit and trash our shiny-ass bikes! I wasn’t sure what would be worse—that, or having Sande scream at me for the next hour about what a blithering a-hole I was. Eventually, she got over it, but mention the word hutong to her even today and she’ll sneer at me.

That evening, we strolled among the street stalls of the Donghuamen Night Market, just a block from our hotel, in awe of the exotic food offerings, which include crickets, centipedes, scorpions and lizards—all served fried on a stick. I nibbled at a scorpion, considering it payback for the fright a very live one had given Sande and me when it found its way into the bedroom of the French villa we had rented in the hills of La Motte-En-Provence several years before. (Another story.) At any rate, I figured nibbling on fried scorpion was better than taking on the full course dinner of snake being offered at a restaurant on that very street. Not only was snake on the menu, but a tank full of live ones slithered in the front window, ready to be hand-selected by the restaurant’s patrons for skinning and sauteing. The Chinese version of westerners selecting their dinner from the lobster tank, I suppose.

As special as Beijing is (special enough to take us back there a few years later), so too was all that had preceded it, as our itinerary for this trip had already taken us to Hong Kong, Guilin, Shanghai and Xian—each of which has its own story, yet all of which paled by comparison to what still lay ahead…the Great Wall of China.

There are certain iconic places that we all know, but few of us actually experience. India’s Taj Mahal, Moscow’s Red Square, Egypt’s Pyramids, the Acropolis in Athens, the Colosseum in Rome—all quickly come to mind. The Great Wall more than holds its own in that esteemed company. To stand on it and observe its seemingly endless meandering reach across the mountain landscape is a true wonder. As Sande and I walk along its circuitous route for over an hour, distancing ourselves from the tourist herds, I envision Genghis Khan’s Mongol warriors attacking from the east and consider the hundreds of thousands of lives estimated to have been lost in the Wall’s construction, before arriving at a clearly-in-need-of-restoration section guarded by a militarily-clad, fireplug of a female “officer” of some sort.

At first, she indicates the international symbol for No Trespassing that is posted, but she quickly transitions to the international symbol for “slip me a few Chinese yuan and you can proceed” by rubbing her thumb and two stubby fingers together. Being westerners accustomed to the concept of tipping our way to ever more unique experiences, we coughed up some yuan.

Our toll paid, we proceeded to crawl through a dilapidated and overgrown with thorny vegetation guardhouse doorway of sorts. We were now officially on the non-tourist wall. Pretty cool…at least until the snake sighting.

Our wall walk now transformed into something more akin to a mountain trek, and we soon arrived at the foot of a very sharp vertical incline—at least a hundred meters rising at an angle of probably 70 degrees—at the top of which we could see another adventurous (foolish?) couple. The route up involved crudely fashioned steps—the horizontal base of each being only a few inches wide but the vertical riser being perhaps a foot and a half high, making the ascent literally a climb. “Forget it,” Sande said in no uncertain terms. “You want to climb it, be my guest. I’ll wait here.” What the hell, I figured. I’d come this far…and paid my hard-earned yuan to get here…so up I went.

The “steps” were so steep that you literally would grab the ledge above you before hoisting yourself up to see what was there, which became problematic when I was about a third of the way up and heard Sande yelling something from below at the same time the couple was yelling something from above. I looked down at her and up at them, trying to translate their “something” into a word. The word became clear to me just as I pulled myself up to eye-level with the next step. The word was snake and my now-bulging eyes were fixed on a large black one, probably four or five feet long. It was not alive but it might as well have been as I damn near jumped off the Great Wall of China before I figured that out. Needless to say, I’d had enough adventure for that day and retreated to the more beaten path of the common tourist. Which leads to my last point.

On our way down from the Wall, we passed several Chinese women who were selling souvenirs, the benefits of capitalism not having been lost on these hard-selling ladies. We bought some sort of Wall bauble, but this one woman kept hawking me to buy more. At this point, I figured I had my story (and a bauble) to take home; I didn’t need a shirt that read: My father went to the Great Wall and all I got was this lousy T-shirt, so I demurred…several times in fact as she followed me half way down the trail, yapping in Chinese. Finally, she gave up, pronouncing: “You a cheap man!”

Ah! Capitalism and English…alive and well, no matter how far from home I may roam.

T H E E N D

Comments (0)